Day 8: It Ends When I Decide |

This is day 8 of journalling with Selena. There is no prompt.

The format for this post was inspired by The King of Boston. Genuinely an amazing read, please check it out.

i. undocumented creature

I accidentally system reset my iPhone while playing lacrosse with my sister over spring break last year. After setting it to Chinese to practice reading a language I’d forgotten, a half hour of jostling around in my pocket left it locked. Impatient and annoyed, I saw a pair of characters that I thought meant “reset password.” With a few button clicks, I’d wiped every single app, photo, and file off of my phone for 4 years.

After the reset, my phone now holds 3,906 items in my camera roll as of today. I have 240 selfies. 403 videos. 25 favorites. Zero duplicates. When I scroll all the way up, I see my six photos from before 2023, my six photos of childhood me.

I didn’t like sitting still, didn’t like posing. I’d tug at my face in response to “picture” or “photo” or “照片.” Relatives would make that familiar smacking ntsssch sound with their tongue when they saw the faces I made in the photo. I’d do anything to screw up being captured. Bunny ears, waving my hands til they became a beige blur, anything to avoid the cage of my mom’s facebook posts or my grandparent’s WeChat 朋友圈. The more I did, the more they wanted to freeze it. Prove it. Post it.

Of the six photos I have, I find it hard to reconcile that they were once me. I still express surprise when my elementary school classmates and teachers recognize me. I don’t know what’s more jarring – the fact that they recognize me, or the fact that I don’t. I look at the photo, and my uncanny valley twin stares back with his eyes that reveal nothing. Someone I used to know, whose name I’d long forgotten.

ii. hot potato, hot potato, we’ve got the hot potato

Some people look at Wikipedia, and some just take the first search result on Google. Little me had something better. I had my dad, who seemed to know everything about anything, whether it was physics or history or math. All his answers lined up with what I’d been taught, and a lot of the time, the only answers I had were what he’d told me.

I had a Biggest Book of Science that I loved reading from, but there were a few passages that made me terrified. One such passage was a quick fact about the sun – Did you know, the Sun will expand in 5 billion years, swallowing the Earth? I started shaking after I read that. I knew from a few pages before that the sun was pretty hot, and it was definitely not a good thing that the sun would swallow the earth. I ran downstairs, panicked and looking for reassurance. My dad laughed.

“Don’t worry, think about it, that’s longer than the whole universe will be around. Life will be different as we know it then.” Satisfied, I ran back upstairs to continue reading, happy that nothing bad was going to happen.

Only a few days later, something else didn’t add up. Reading some book about humans and climate change, I showed my dad a graph of CO2 and oil consumption. The book foretold catastrophe – rising sea levels and mass extinctions, a total upheaval of everything we humans knew the Earth to be. How could this be? I’d just gotten over the fact that the sun would explode in 5 billion years, and now they were telling me the clock was ticking way faster. I scampered downstairs to do some cross-validation. The answer I got?

“It doesn’t really matter.”

Huh. An uncharacteristically short response. Maybe I’d have to do more research. Maybe on the next page my book would agree, saying “Sike, your dad’s right, it’s all good.”

I read two more pages, then ran downstairs with more findings to confirm. “Baba, baba, is it true that by 2075 if things don’t stop these things could be irreversable?”

“So what?”

So what? I still thought that everyone automatically lived to 100 years old, and I could do the math: I’d definitely still be alive in 2075. “Isn’t it scary? We have to do something!”

“You do. I’ll be dead by then, it doesn’t matter to me.”

Some quick mental calculations confirmed that he’d be 99 years old by the time 2075 rolled around. Fine, I thought. It’s no different from the sun’s explosion not mattering… I think.”

iii. when i go

On the four hour drive back from school, I sat in silence, cruising down the I-95. Again, my dad snapped me out of my reverie.

“I think I’ll commit suicide when I’m seventy or something.”

I gripped the steering wheel and let the words linger.

“Or, what’s the word? Youth In Asia?”

“Euthanasia,” I corrected.

“I’ve told you before that I don’t want you to put me on any ventilators or anything, all those tubes going in and out of my body. If it’s time for me to go, I’ll go. And maybe I want to do it on my own terms.”

I nodded. “Why seventy?”

“I don’t want to be in pain and live a life hobbled. I’ll either live, or die. That’s that.”

I nodded again. The math didn’t lie. It told me 21 years remained.

My sun exploded again.

But then, I think of my great-grandmother. She was 88 the last I saw her. She didn’t know who I was, that her grand-daughter had a son. I knew very little about her, only that she’d raised my mom, and that she’d hid in the caves when WWII came. My mom said she saw her neighbors head get taken off by a bomb. Being a WWII obsessed kid, when I finally met her in Wuhan, I stared in awe, not daring to ask what it was like.

She lived alone in an apartment on the third floor. Her face was wrinkled, each fold like a tree’s ring. I’d read somewhere that a tree’s rings could tell stories, and I studied her face to read what secrets it held.

My mom considered having her come to the US to live with us. What kind of a granddaughter could send the woman who raised her to a senior home, when all that was expected of you was that you take care of them as they got old? But maybe it was the visa that fell through, or maybe she wanted to stay in Wuhan. She never did come to the US.

Her bathroom faucet dripped, no matter how hard I tried to tighten it. Likewise, her memories and cognition dripped too. My mom flew out to China to see her in April. I don’t think my great-grandmother remembered her. On a WeChat video call, I studied her face again. Now, it was as if she’d aged backwards. Her wrinkles stretched across her gaunt skeleton. My mom cried. 五十斤, she’d sob. Fifty pounds. She weighed less an elementary schooler. Her mouth lay open agape, opening and closing as if gasping for air. My mom fed her congee, and she could not swallow. I couldn’t swallow either.

I looked away, but the beeping of her heart rate monitor reading 84% oxygen saturation and my mom’s gasps did not let me leave. I finally asked: “Can she still speak?”

My moms sobs grew louder. My great-grandmother groaned.

One year later, she is not yet dead. She is immobile, catatonic, dreaming, a log on a hospital bed. My mothers calls go unanswered. Though her heart still beats, her eyes have not opened for months. Maybe I could understand why my dad wanted to go on his own terms. But twenty one more years are too short. Twenty one years is no time at all. After all, I’ve been around seventeen, yet it hardly feels like I’ve been around for that long at all. If living is thinking, choosing, doing, then I’m just getting started.

iv. history 300

I was told to take history 300 senior year, but I decided to stick it out upper year. When my mom found out, she called me, incredulous. She said I’d regret it, that it’d take up too much time, and that I should be focusing on science or whatever it was that would make my transcript actually strong. I didn’t listen, and I didn’t have a good reason as to why I didn’t, just that it felt weird to push it back.

For homework, we submitted primary source set responses (PSSRs), on artworks, on testimonials, on photos, on music, and answer questions looking at the material from a variety of lenses. What was being said? What was left out? How did this tie into what we were learning? These low-stakes writing assignments were supposed to be unpolished, a quick snapshot of thinking and reflection, an easy way to develop voice as a writer.

As I did so, I started thinking about finality. About what it means to take a photo or paint a portrait and never edit it again, to leave it, final, for the world to see, to poke, to prod, to analyze in PSSRs and debate in classrooms.

It must be terrifying, I thought. To hit publish, to be studied, to give something up like that and hope you weren’t misunderstood.

And writing this blog, I felt the same way when my mom told me she read my posts, and that she didn’t really get them. I nodded and agreed, but I was horrified. How could I let her see what I wasn’t even done with? How could I let anyone see what I wasn’t done with? Last night, I edited a lot of them in the hopes that no one else reading them would have the same feeling, that they wouldn’t text me saying, hey, I didn’t really get what you were trying to say with that ice cream post. And yet, for all the fear of finality – of putting something out there and never being able to take it back – I found that constant revision had its own burden.

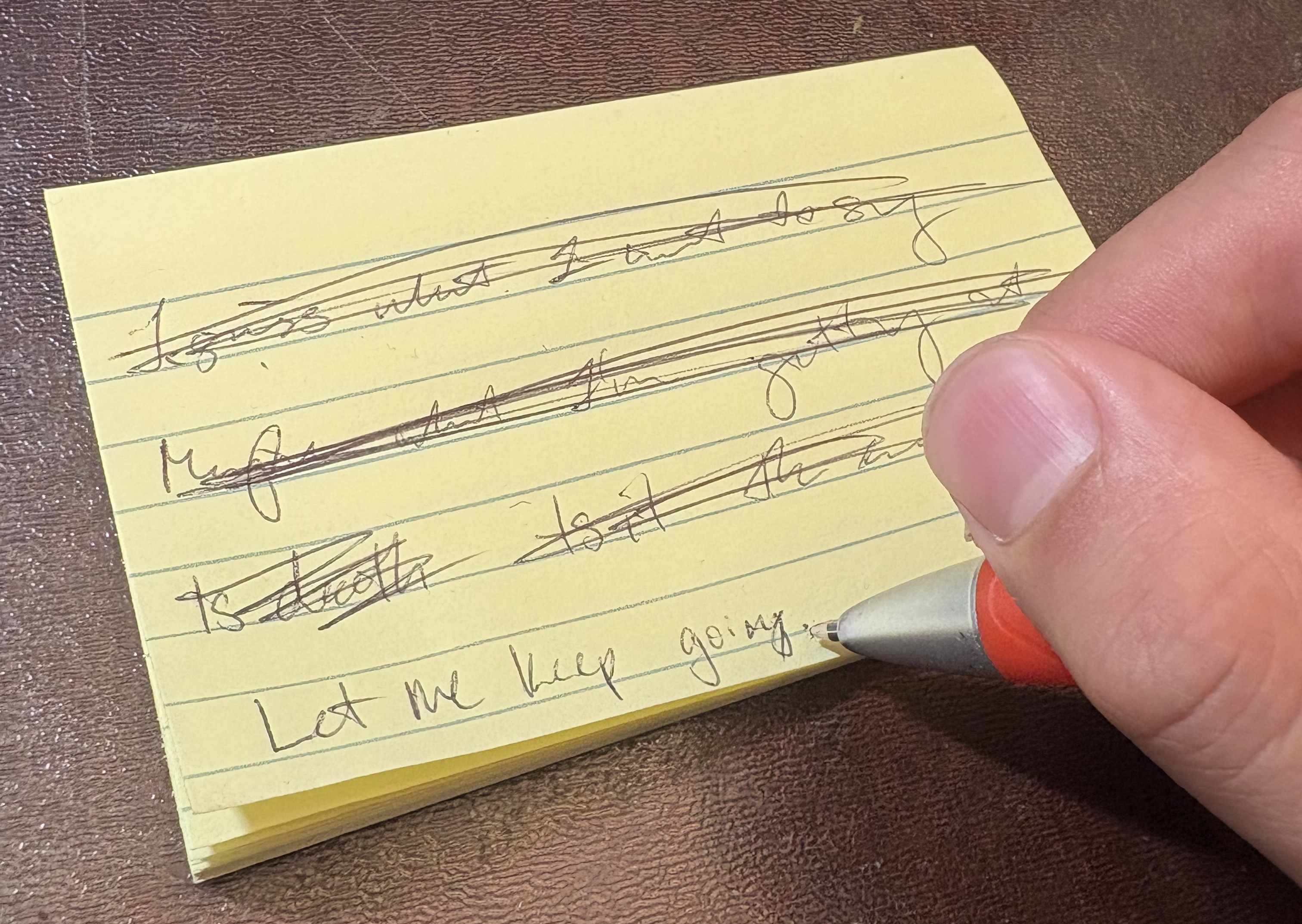

At the end of each term, we’d gather all our PSSRs and mark them up, writing reflections on themes that emerged, and what we hoped to improve on in the next term. I thought I’d like it, that I’d feel growth and improvement, that I’d feel proud of my little snapshots, but oftentimes the scramble felt like regret. I held up a prior version of myself and my thoughts, and I took highlighter and graphite to point out what I’d done and what I hoped to do better. I scoffed at what I was happy with weeks ago. Pshhh, how could I even think this way? What a totally out-of-touch take. It always felt fake to write about a theme that emerged, because all I could think was that I sure didn’t do a good job at analyzing. Every end of term reflection felt like regret. Like hatred. And even more than that, I was angry at feeling regret. After all, the whole point was to take a snapshot of the moment.

So now, I fear something else, more than just hitting “publish” or typing “git push” in the command line. I fear the moment when there’s nothing left to revise, when there’s no more chances to look over it that one more time. Because to revise is to still be alive. And if I couldn’t even love the revision process, I might as well’ve been dead already.

v. even in death

“Be cheerful, sir.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.”

Before Shakespeare died, he wrote The Tempest – a play that opens with a storm and ends in quiet. Some argue that his epilogue was not only a character’s farewell to the stage, but Shakespeare’s as well. Others say he didn’t mean anything by it.

As I reread my blog posts, my writings from last year, the cringy way I’d text in old text messages, and look at photos of a boy I hardly recognize, I wonder what Shakespeare would’ve done with an edit button. If he ever wished he could take it back.

But even in death, his words are not final. We read his works through post colonial, queer, anti-capitalist lenses. We find new meanings in the same old lines. We revise him, even long after his bones have returned to earth.

Maybe nothing is ever final – not because we live on, but because others keep rewriting us. We become their interpretations, their blog posts, their PSSRs. And maybe they’ll get us all wrong. That’s the paradox – we crave control over our narrative, yet must accept we’ll never fully have it.

Sometimes, turning in an essay feels like a white flag to me. I surrender my typos, my flaws, and that’s that. I know someone else will read it, mark it up, maybe misread what I meant entirely. Maybe they’ll miss the point. Maybe I missed the point. And maybe I could’ve made it just that little bit better, because I know that in my subconscious, turning it in half-meant that I’d given up entirely. That I’d dropped the hot potato, passed the consequences on, hoping someone else would clean up the mess.

But I’m still here, still thinking, still writing. I won’t get it all right, I won’t even get most of it right. But while I still can, please – hand me the pen, the Photoshop, the edit button. I want to revise the story while it’s still mine. I want to catch the hot potato and hold it, even if it burns.

I’ll never do it all. But hey, that’s life, and it’s death too.

Prospero’s Epilogue

Now my charms are all o’erthrown,

And what strength I have ’s mine own,

Which is most faint. Now ’tis true

I must be here confined by you,

Or sent to Naples. Let me not,

Since I have my dukedom got

And pardoned the deceiver, dwell

In this bare island by your spell,

But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands.

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant,

And my ending is despair,

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardoned be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

An update from 7/19/2025: My great-grandmother passed away today at the age of 97. She was admitted to the ICU after her blood oxygen was found dangerously low. It turns out, she’d been unable to swallow food properly, and it had gone into her lungs instead.