This is a 3d projection of 72,000 English words in Word2Vec. Every point represents a word, and the distance between them captures (or at least, tries to capture) semantic difference.

So what? How do the points represent words?

TLDR: This is actually super relevant now, as this is an old model for how generative AI encodes words. AI models assign words large lists of numbers and do operations with those numbers to predict what to say.

Click to expand a longer explanation.

The idea behind Word2Vec is deceptively simple: words that appear in similar contexts tend to have similar meanings. Instead of trying to define what a word is, Word2Vec learns what words do based on how they behave and where they co-occur in real text. It slides a small window across text and learns to predict nearby words from a given word (or vice versa). Over time, it adjusts a set of numerical vectors so that words used in similar contexts end up with vectors that cluster together.

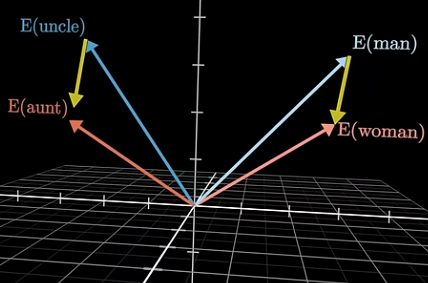

This process turns language into geometry. Words that appear in similar contexts often land near each other in the high-dimensional space, because they share linguistic environments, and therefore, meanings. More impressively, Word2Vec captures relationships as directions: the famous example is that the vector difference between king and queen roughly matches the difference between man and woman.

So why does this matter for AI today? Modern large language models (LLMs) like GPT or Gemini are way more sophisticated than Word2Vec, but the core idea of representing words as vectors that encode meaning is still foundational.

Ok, cool. So what does this have to do with Turkish and Finnish?

TLDR: Turkish and Finnish build words by using lots of suffixes, and sometimes it’s more efficient for AI’s to break up words into smaller tokens (tokenization) to better understand the text.

Click to expand a longer explanation.

While English typically forms meaning through relatively short, separate words, Turkish and Finnish are highly agglutinative languages: they build words by attaching multiple suffixes to a root, sometimes stacking many layers of grammatical information into a single long word. This creates challenges for language models. If you tokenize purely at the word level, many unique word forms appear extremely rare or entirely unseen in training data, even though the underlying root or morphemes are quite common.

"Evlerimizde" = "In our houses"

"ev" = house, "ler" = plural, "imiz" = our, and "de" = in

By breaking words into smaller subword units, models can better generalize across these variants. Going back to Word2Vec and other similar embedding models, all of these systems are heavily affected by tokenization because the "units" they learn from depend on how the text is split. In agglutinative languages like Turkish and Finnish, thoughtful tokenization = robust representation of morphemes (prefixes, suffixes, infixes, and roots) rather than treating each agglutination as an entirely independent word.

I see. So which ways did you end up tokenizing your text?

TLDR: I used character-level segmentation, character n-grams, word level, and Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) with vocabulary sizes of 5k, 10k, 25k, and 50k. Byte Pair Encoding is a popular tokenization method that merges common pairs of characters until a certain vocabulary size is reached.

Click to expand a longer explanation.

Let's break down each tokenization strategy in a bit more detail:

Character level is super simple. All it is is segmenting every single character. "Hello World!" becomes [H, e, l, l, o, " ", W, o, r, l, d, !] Obviously, this is not going to give you very good results with most languages. Your entire vocabulary is going to be a few dozen characters, and your model is just not going to learn meaning from this.

Character n-grams is a bit better. What it does is it takes every n characters and treats it as a token. For example, for bigrams (n = 2), "Hello World!" becomoes [He, el, ll, lo, "o ", " W", Wo, or, rl, ld]. Now, this is a little bit better than character level, but having all words be a certain length is still certainly not ideal.

Word level is also super simple. Just segment by word, no matter how long. "Hello World!" becomes [Hello, World!]

And now, for the fun part: BPE. BPE was the gold standard for tokenization strategies until about 2021, when other strategies such as BERT, ULM, byte-level BPE, etc. have marginally improved over BPE. What BPE does is it starts with character level tokenization. So for example, if I'm dealing with text with the English alphabet + commas + periods, my text will have a vocabulary size of 28 tokens. Next, we merge the most common pair.

For example, “abcbabcbab” would be merged as follows: "a” + “b” = “ab” “c” + “b” = “cb” “ab” + “cb” = “abcb”, and so on. In a real corpus of text, there'll obviously be a ton of different merges, which organically begins to approximate prefixes, suffixes, and full root words.

Ok, got it. So you where are you getting the text from and how do you compare the strategies once your Word2Vec models are trained?

TLDR: You can easily scrape Wikipedia articles in both Turkish and Finnish, and you can train a simple model on the Word2Vec models to do something called Named Entity Recognition (NER). I used the accuracy on NER to compare efficacy.